Apr 26, 2024

A Dubai Firm Pledged $13 Billion for 20 Years of South Sudan Oil

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- A little-known company run by a distant relative of the Abu Dhabi royal family agreed to lend 12 billion euros ($12.9 billion) to South Sudan in exchange for repayment in oil, making it one of the largest ever oil-for-cash deals and the latest such intervention in a struggling African country.

According to an unpublished report by a United Nations Security Council-appointed panel of investigators reviewed by Bloomberg, the Dubai-based Hamad Bin Khalifa Department of Projects, or HBK DOP, and South Sudan’s then-finance minister Bak Barnaba Chol appear to have agreed to the terms of the loan in documents signed between December and February.

The deal amounts to almost double the GDP of South Sudan, which has been ravaged by famine and conflict, and 70% of the funds are earmarked for infrastructure, according to the documents seen by the investigators. But a loan of this size — about five times the country’s current external debt — also would likely tie up most of South Sudan’s oil revenues for many years, the unpublished report says.

For HBK DOP, which was founded by Sheikh Hamad Bin Khalifa Al Nahyan, a distant member of Abu Dhabi’s royal Al-Nahyan family, the loan may lock in access to oil at a discounted price for up to two decades. Under the agreement, South Sudan will receive $10 less per barrel of oil when compared with an international benchmark price.

“This would be a very significant bet on this particular partnership that would have repercussions through multiple administrations,” said James Cust, a former senior World Bank economist and visiting lecturer at the University of Oxford. “It’s a big deal, and it’s going to run and run.”

It’s not clear whether the first $5 billion installment of the loan has been delivered, and attempts to reach HBK DOP for comment haven’t been successful. In 2021, HBK’s bid for an ownership stake in an Israeli soccer club was frozen after the league raised questions about his net worth and investments.

South Sudan’s current finance minister didn’t respond to a request for comment. Chol, who was fired by President Salva Kiir in March amid local media reports of worsening economic conditions, declined to comment. The country’s information minister wasn’t immediately reachable by phone and the UAE government media office hasn’t responded to a request for comment.

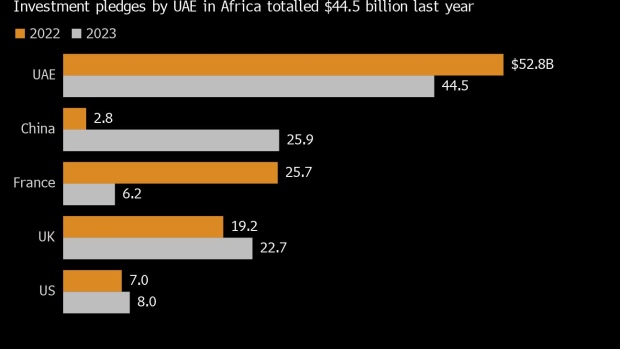

The loan comes amid an aggressive expansion by Gulf countries and regional businesses into new markets. In February, the UAE offered Egypt a $35 billion lifeline, and it has pledged more investment to African countries than any other region.

Oil-backed loans can be an attractive option for resource-rich developing countries, which often struggle to access large-scale traditional financing. In theory, if the borrowing is transparent, the terms favorable and the projects well-selected, they can generate positive returns.

But they are risky. About a decade ago, a $1.5 billion loan to Chad from Glencore Plc and other syndicated creditors brought the country to its knees after the oil price dropped and the government was forced to divert its primary revenue stream to repaying the Swiss trader. A portion of the debt still hasn’t been repaid, and disputes with Glencore helped delay the country’s latest bailout from the International Monetary Fund. Similar deals have sent other oil producers, including the Republic of Congo, into debt distress.

Akinwumi Adesina, president of the African Development Bank Group, has described resource-backed loans as “a disaster for Africa.” IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva has said they can be “predatory and enslaving.”

South Sudan has a problematic history of such deals and has lost court cases for failure to repay. UN-appointed investigators found previously that, for $446 million in credit, South Sudan paid $95 million in fees, interest and costs. That resulted in a loss of almost 25% of potential government revenue, compared with if the oil had been sold through spot tender contracts, the investigators said in a report published in April 2021. Oil exports account for roughly 90% of the country’s income.

In 2019, South Sudan agreed to forego new oil-backed arrangements in order to secure a $52 million support package from the IMF. The decision coincided with a statement from the IMF that oil-backed loans are “non-transparent, costly, encourage misuse and complicate fiscal management.”

UAE-based companies have been regular creditors to South Sudan. In 2022, UN-appointed investigators reported certain loan proceeds were paid into South Sudan government accounts in the UAE, rather than into the country’s designated oil revenue account.

Chinese state and private companies, as well as international commodity traders, have been most hungry for African resource-backed loans in the past. The duration of the UAE firm’s loan places it closest in profile to previous Chinese deals, Cust said. “This is really getting into the more structural model that we've seen dominated by China in the past,” he said.

In their most recent report, the UN-mandated investigators raise concerns that South Sudan continues to contract oil-for-cash loans. “Despite South Sudan’s difficulties managing oil-backed debt, the panel has reviewed documents that indicate the government is negotiating what would be its largest ever oil-backed loan,” the investigators wrote.

According to the panel, the loan documents don’t appear to have been approved through the country’s official channels, including the technical loans committee or the country’s parliament — although that’s not uncommon. Those negotiating oil-for-cash loans have often failed to include the relevant ministries or to notify parliament, the investigators wrote previously.

The HBK DOP loan, which was negotiated on the sidelines of the COP28 climate summit in December in Dubai, may force South Sudan to continue producing oil until at least 2043, years beyond the lifespan of the country’s existing oil wells. After an initial three-year grace period, the loan will be secured against the delivery of oil for up to 17 years, the investigators said.

“If it turns out to be a bad deal for South Sudan, that's a stonking great carbon subsidy that they're providing to the market,” Cust said.

--With assistance from Abeer Abu Omar, Paul Richardson and Okech Francis.

(Updates with additional comments from former World Bank economist in 15th paragraph.)

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.