Apr 19, 2024

Troubled Borrowers Seen Fighting for Runway Without Fed Cuts

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The surprising resilience of the US economy would seem, on the face of it, to be good for corporations. But as the expansion plows ahead, pressures are forming beneath the surface to threaten some of the country’s riskiest companies.

Many heavily indebted corporate borrowers have been able to kick their problems down the road, refinancing debt or reworking terms amid buoyant credit markets. With a slew of Federal Reserve interest-rate cuts once widely expected, their thinking was that they wouldn’t have to wait long to gain breathing room to repair their balance sheets.

That strategy is unraveling as a relentless string of hot economic data pushes back the expected timing of rate cuts, and even calls them into question. Now, struggling companies instead face an extended period of elevated borrowing costs, pinched cash flows and rising defaults.

“Today, everyone wants to amend and pretend because they believe it’s going to get better,” said Ranesh Ramanathan, co-leader of Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld’s special situations and private credit practice. “At some point, you can’t.”

It’s already starting to bite: A number of private-credit funds had their outlooks lowered to negative from stable by Moody’s Ratings this week because of concerns about potential losses on their corporate loans. Yields on some of the lowest-rated US junk bonds are approaching 13%, marking a four-month high. Also troubling, key metrics such as interest coverage ratio, a measure of how much cash a company has available to pay its interest, are deteriorating, according to Ramanathan.

While the pace of bankruptcies this year has been unremarkable overall, a one-week stretch this month saw the most large insolvency filings in 15 years, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

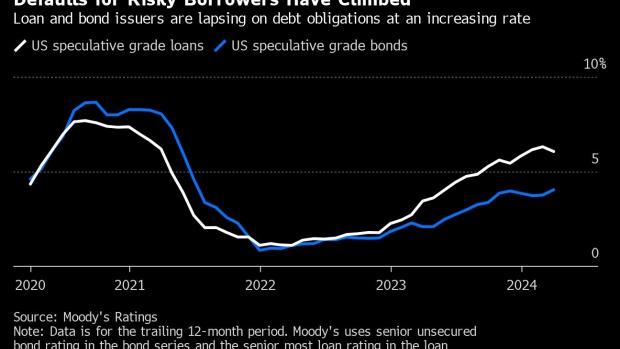

To be clear, the situation isn’t yet near a crisis point. Default rates — while ticking higher — aren’t at alarming levels. Lenders remain generally receptive, most companies generate sufficient cash to service their debt and the continued strength of the consumer is still a boon to businesses.

But cracks are starting to form as the expense of managing heavy debt burdens puts a squeeze on finances. These pressures raise the risks that an economic “landing” — if and when it comes — will be a hard one.

“All the cash that was going to enhance and grow a business is now going to pay interest, which does nothing to help the company,” said Ron Kahn, co-head of the valuations and opinions practice at Lincoln International, an investment banking advisory firm.

Some challenged companies have seized a still-open window for credit to refinance their obligations — but it’s coming at a cost. Nutritional company Herbalife sold $1.2 billion in bonds and loans at steep discounts to clinch a refinancing earlier this month. The company will have to pay a 12.25% coupon on its new notes, and the leveraged loan priced at 6.75 percentage points over the benchmark.

‘Tough Time’

KKR & Co.-backed Global Medical Response is refinancing more than $4 billion of debt in a complex transaction that involves a $3.6 billion amend-and-extend first-lien loan, $600 million in new notes and $948 million in preferred equity. S&P Global Ratings downgraded the company to CC from CCC+, describing it as a distressed transaction.

Those distressed deals are often not one-off situations, according to Moody’s. The credit ratings firms categorize distressed exchanges as selective defaults, which contribute to the default rate. Research from Moody’s found that 40% of companies that defaulted in 2023 were previous offenders, a trend they expect to continue.

“These companies face a tough time given conditions of low growth, inflation and persistently high interest rates,” Moody’s analysts led by Julia Chursin wrote Tuesday.

The riskiest cohort of credits, those rated CCC, have faced painful losses as the higher-for-longer reality looks increasingly clear.

“For 85% of the market, they’re doing fine, the economy is doing fine, given it’s not a recession or hard landing,” said Jason Friedman, partner and global head of strategy and business development at Marathon Asset Management. “It’s that 10-15% tail of the market that really has trouble the longer rates stay high.”

Friedman said Marathon’s capital solutions business has “never been busier.” Requests for payment-in-kind debt and other creative solutions started to increase in the third quarter of 2023 and have picked up recently, he said.

Private equity-owned companies, in particular, are hurting after a failure to hedge their floating-rate borrowing costs during the easy-money era. As monetary policy tightened, they turned to financial engineering to deal with their immediate problems, securing loan extensions and taking out more expensive forms of debt in the hope of shrinking the burdens when rates began to fall.

Now, that “Survive Til 25” mantra is being upended as the expectation that borrowing costs would fall fails to materialize.

Read more: Hedging Failure Hammers Private Equity as Debt Costs Skyrocket

“PE performance, dating back to the beginning of 2022, remains negative, highlighting the difficulty of generating attractive investment returns in a higher interest rate and lower multiple environment,” according to a report by McKinsey & Co. last month. That’s far below the double-digit annual returns that investors expected when they allocated money to managers who could seem to do no wrong when rates were lower.

In one part of private credit, the default rate was a benign 1.84% in the first quarter of 2024 after ticking up over the last year, according to the Proskauer Private Credit Default Index. That dataset offers a view into nearly 1,000 middle-market loans to companies with an average annual Ebitda of around $50 million.

These mid-size companies have overall adapted to higher interest rates and have held up since the Fed started raising rates in 2022, said Stephen Boyko, a partner at law firm Proskauer Rose LLP. “We’re two years in at this point, and we’re still seeing revenue growth and Ebitda growth,” Boyko said.

While default rates will continue to increase in the coming quarters, Boyko doesn’t expect private credit defaults to reach anywhere close to the levels of the leveraged loan market. That’s because private credit lenders have more control through covenants and typically tend to hold the debt, rather than trade it, making them more invested in the outcome, he said.

That control could have the effect of masking distress, though. Managers and the sponsor-owned businesses they lend to have several levers at their disposal to avoid defaults and paper over problems in their big portfolio bets.

Amendments on Rise

Amending a company’s credit agreement to waive a covenant, allowing a company to pay interest in kind or to extend maturities has been on the rise this year. Roughly 18% of 1,500 companies tracked by Lincoln International in their private market index received one or more amendments. In return, roughly 30% or more of those amendments were accompanied by an infusion of cash from the sponsor, supporting liquidity.

“We believe a lot of the amendments are anticipatory as no one wants to report defaults and would rather amend the loan agreement,” Lincoln’s Kahn said.

Even as ratings firms proceed with downgrades and warnings, those decisions are happening at a lag to the true pain companies are feeling.

“It’s like an ambulance coming to a funeral home,” said Dan Zwirn, chief executive officer at Arena Investors. “These things are on a big lag because the amount of incentive to resist recognizing the reality is enormous.”

--With assistance from Abhinav Ramnarayan.

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.