Apr 26, 2024

Thames Water Crisis Puts £100 Billion UK Investment Plan at Risk

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The debt crisis at Thames Water is jeopardizing £100 billion ($125 billion) of potential investment required over the next five years to mend Britain’s crumbling utilities infrastructure.

Water companies have promised to deploy the sum to fix leaky pipes, build new reservoirs and prevent sewage from pouring into the country’s seas and rivers, according to water regulator Ofwat. But investors warn the money may not be readily available if the government forces losses on Thames Water creditors.

The standoff over what to do with the UK’s biggest water and sewage company has reached a stalemate, with shareholders refusing to inject more capital and the government insisting that taxpayer money shouldn’t be used to resolve the crisis. As the impasse wears on, it’s becoming increasingly likely that the firm will be taken into temporary government ownership, a move that could involve writedowns on even the safest bonds of as much as 40%.

Investors have historically been willing to lend to British water companies at relatively low rates in exchange for stable returns, which are usually set by Ofwat. Average borrowing costs across the sector have jumped to around 7% from 6.2% at the start of the month, implying that trust in that contract is already weakening.

“An erosion of confidence in a regulatory regime would increase the cost of debt, not just in the water sector but more generally,” said a spokesperson for Royal London Asset Management Ltd, a British money manager that holds assets in a number of UK water companies including Thames Water. “Whilst investment will be available to support future infrastructure investment, the return required by pension funds will be higher if confidence is lost.”

How Debt and Sewage Pushed Thames Water to the Brink: QuickTake

Short Sellers

The government needs to keep investors onside if it is to achieve an ambition set out by Chancellor Jeremy Hunt in his Mansion House speech last July to release £50 billion of private long-term capital for infrastructure projects. That money is badly needed, not just for the water sector, but also for implementing upgrades to the UK’s rail and broadband networks and energy grid without passing on all the costs to consumers.

The UK’s water industry may struggle to attract fresh financing should Thames Water’s senior bondholders end up facing losses, according to a survey of investors by Barclays Plc. Highly-leveraged companies from across the UK water sector are already being targeted by short sellers as contagion from the Thames Water crisis causes borrowing costs to rise.

“Thames is not a good advert for investing in private equity infrastructure, and it’s happening just as the government is trying to get UK pension funds to invest more,” said John Ralfe, an independent pensions consultant who was previously the head of corporate finance at UK retailer Boots.

Public outrage over mismanagement at Britain’s water companies and sewage spills into the country’s waterways means the government is reluctant to be seen being too soft on creditors. “What we’re never going to do for investors in the UK, is say that the state is going to insure against bad decisions made by management or shareholders. That’s what markets are about,” Hunt told reporters in April.

Some within government believe a debt restructuring could even make Thames more attractive, according to people familiar with discussions who asked not to be named. They point to investors’ notoriously short memories as a counterpoint to creditor warnings, the people said.

Gordon Shannon, a portfolio manager at TwentyFour Asset Management LLP, says a writedown could be justified by a “defensible trigger” such as a ratings downgrade.

“That’s a clear line in the sand that can give other investors some comfort,” Shannon said. “Do it that way and I think we can get through without too much damage to overall sector sentiment.”

Leaky Pipes

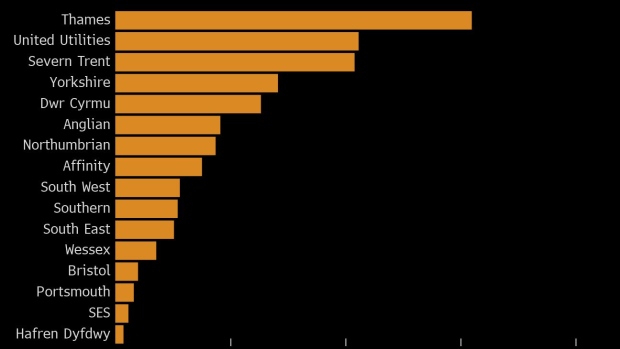

The government is playing a risky game, though. Thames Water, which has the highest number of leaks of all of the UK water companies, has no way to fund essential repairs and upgrades without financial support from shareholders.

Thames’ shareholders this year submitted a proposed return that works for them to deliver the necessary investment. But it requires a 56% increase in bills over five years, or 40% excluding inflation. Ofwat proposed a 25% lower return, which Thames owners declared unworkable.

The regulator’s plan gave shareholders worse terms than bondholders, despite bearing the greater risk, according to Thames Chief Financial Officer Alastair Cochran. “You have to ask yourself, why would an equity holder take on a lower return than buying a bond in the market?” he said last month.

“We need to ensure that the sector attracts investment and is fair to bill payers,” an Ofwat spokesman said by email on Thursday. “We also need to see companies deliver the performance that customers expect and that they are run in a way that meets customers’ expectations.”

Investors will reassess the risk involved in lending to infrastructure assets, including airports and rail, if the government forces them to wear some of the costs of the Thames restructuring, according to a recent paper by the EDHEC Infrastructure & Private Assets Research Institute.

Currently, there’s no inclusion for political or default risk in Ofwat’s regulatory price formula that determines the return on equity for owners. If Thames is wiped out, Ofwat will have to overhaul or incorporate these risks into its models, which would ultimately push up bills for consumers, EDHEC research director Tim Whittaker said in an interview.

It’s possible that by restructuring the debt, the government could justify lower returns for any new owners. That way, Ofwat would be able to hold down bills and get the desired investment. But the danger is that the financing model will by then be fundamentally different and new investors would no longer be able to trust the regulatory framework, demanding better terms and therefore higher bills.

Or worse: The Thames fiasco becomes a cautionary tale for any investor in Britain’s regulated industries.

“Previously, the assumption was that investors were protected, resulting in low interest rates,” Whittaker said. “Now these assets have become riskier.”

--With assistance from Jessica Shankleman.

(Updates to add details of Ofwat proposal from 14th paragraph.)

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.