Apr 16, 2024

Brazil Makes First Ethanol for Green Jet Fuel, Rocking US Rivals

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The US made a huge technological leap forward this year with the launch of the world’s first plant that makes sustainable jet fuel from ethanol — but it’s Brazilian farmers, not American ones, who’ll initially reap the benefits.

Although the LanzaJet Inc. facility in rural Georgia is able to process ethanol made from American-grown corn, it will likely run on mostly sugarcane ethanol imported from Brazil when it first ramps up to commercial production. That’s because many of the largest Brazilian mills have already been certified to make feedstock for sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) that meets official international and domestic standards.

Sao Martinho SA says it expects to be first to be able to supply the US’s nascent SAF market. It has received the necessary certifications — including the globally accepted Corsia standard, established by the United Nation’s governing body for aviation, plus registration with the US Environmental Protection Agency — and has started to make SAF-compliant sugarcane ethanol for export, Chief Executive Officer Fabio Venturelli said in an interview. The company will churn out between 13 million and 15 million liters this season (about 3.4 million to 4 million gallons), he said.

Read more: Scarce Fuel Sources Challenge Aviation’s Climate-Friendly Vision

“The time has come for us to receive due recognition for our work,” Venturelli said. To be eligible under Corsia — the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation — producers must guarantee the ethanol was manufactured with low-carbon emissions and didn’t contribute to deforestation. The EPA requires producers to prove volumes can be stored and transported separately from other fuels.

The race to supply the ethanol feedstock for SAF is critical, as ethanol’s traditional key market — cars with internal combustion engines — has been threatened by the rise of electric vehicles. With about 40% of US corn today supplying domestic mills making ethanol for use as a transportation fuel, farmers and mills alike are anxious to compete in lucrative new markets like low-carbon jet fuel.

It’s not a sure thing: While seen as a way to help decarbonize aviation, SAF is still facing an uncertain future as limited feedstock availability, high costs and a lack of technological diversification pose a challenge for the new industry, according to BloombergNEF. But pull it off and it has the potential to be big. Feeding the world’s green aviation fuel plants that use ethanol as feedstock would require as much as 9 billion liters per year by 2030, producer Raízen SA estimates — nearly a third of Brazil’s entire cane ethanol output.

Read more: Brazil’s All-Powerful Sugar Industry Sours the Country on EVs

Raízen, BP Bunge Bioenergia and mills linked to Copersucar SA have also snagged the Corsia certification. Raízen and Copersucar have registered with the EPA as well, the companies said.

“We are ready to supply ethanol in different spots in the US for sure,” said Paulo Neves, a vice president at Raízen, a joint venture between Cosan SA and Shell Plc.

LanzaJet’s plant, which has been supported by the US Department of Energy, has been using US corn ethanol during the testing and commissioning phase, and Chief Executive Officer Jimmy Samartzis has repeatedly said he aims to use the biofuel ingredient again when improvements are made to its carbon intensity. It’s also critical the Biden administration make changes to recognize greenhouse-gas reduction practices already taking place in making US corn ethanol, Samartzis said by e-mail.

Read More: How Aviation Is Trying to Clean Up Its Dirty Image: QuickTake

“We have made it a priority to continue to pursue American ethanol as improvements are made to its carbon intensity,” Samartzis said. In addition to sugarcane ethanol, the plant will use a range of other low-carbon types of ethanol, such as cellulosic, to produce SAF when it moves to commercial production.

Several of the so-called “alcohol-to-jet” plants planned in the US are expected to be located near the US Gulf Coast, where imports will be more economical. When LanzaJet formally unveiled its facility in January, corn and ethanol groups in the US — the world’s biggest corn and ethanol producer — were quick to decry the lack of low-carbon US ethanol available to be used at the plant. Members of the US industry saw the opening as a wake-up call to move much faster to shrink greenhouse gases across the production chain.

“Plants are not in the US Corn Belt. So the doors are already open for the most competitive ethanol,” said Ricardo Carvalho, commercial director for BP Bunge, a JV between BP Plc and Bunge Global SA. BP Bunge’s production and shipments for SAF haven’t started yet, though the goal is to start later this year. It could export up to 500 million liters of ethanol for SAF once more sustainable jet fuel plants come online, the company said.

The US ethanol industry is racing to level the playing field, including by supporting massive carbon-capture and storage projects that would make ethanol from US corn with a low enough carbon-intensity score to participate in SAF. It is viewed by some as a crucial step to shrink the industry’s carbon footprint, but some of those projects are facing opposition from environmentalists and landowners, meaning they can take longer than initially expected.

“When we look at the emissions chain for US corn ethanol,” said Tomas Manzano, CEO at trader Copersucar SA, “they are not there yet.”

To be sure, Brazil still has work to do. A lot of Brazil’s ethanol is transported in trucks, which can mean more carbon emissions. There are some ethanol pipelines, but they do not reach the country’s main port yet. In Sao Martinho’s case, the company said emissions related to transportation will be lower due to its use of railways.

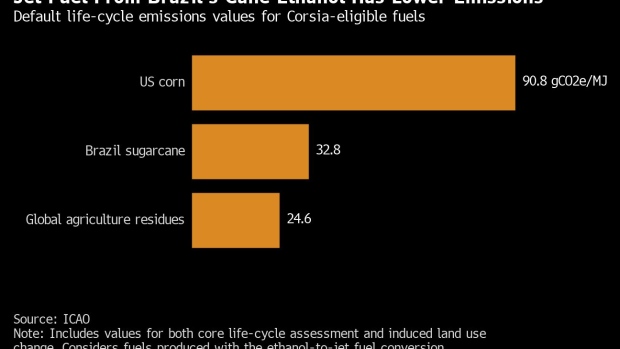

Corsia documents show life-cycle emissions of US corn ethanol are almost three times higher than those of Brazilian sugarcane ethanol. In the US, biofuel makers and farmers are nervously awaiting an overdue update of the Energy Department’s so-called GREET model for tracking climate pollution through the supply chain. Supporters of that approach claim it’s more flexible and up-to-date than the UN approach. Revisions to GREET — which stands for the Greenhouse Gases, Regulated Emissions, and Energy Use in Transportation — are expected to be released soon and could go a long way in determining if US ethanol in its current form will be able to qualify for federal tax credits for making SAF.

--With assistance from Kim Chipman.

(Updates with context in 6th paragraph)

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.